Archaeologist Denise Schmandt-Besserat, a professor emerita of Art and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, and author of the books

Before Writing, Volume 1

and

Before Writing, Volume 2

has been a key archaeologist excavating the Ain Ghazal (Spring of the Gazelles) site.

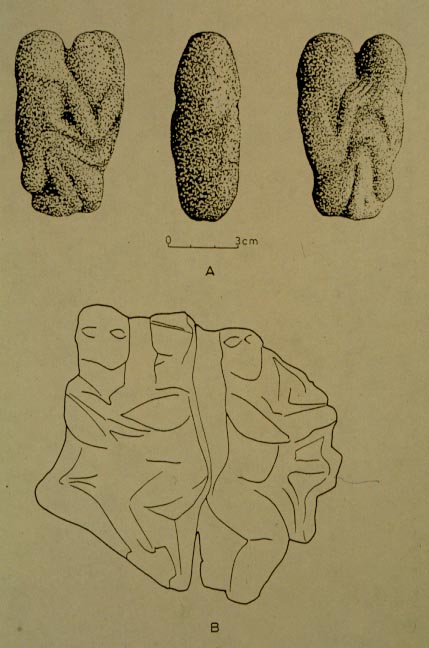

She describes one of the stone figurines with precision. It has "deep, clearly marked

horizontal grooves," she notes, that "divide the body into three parts, the abdomen again occupying

the center. Finally, the stomach is bracketed between a triple set of diagonal

lines. The grooves descending along the breasts widen towards the abdomen  driving the eyes on to it. In the opposite direction, the little arms form a

double set of parallels that emphatically close the center of attention below

the pregnant womb."

driving the eyes on to it. In the opposite direction, the little arms form a

double set of parallels that emphatically close the center of attention below

the pregnant womb."

Continues Denise, "The most

masterful part of the composition is the successful blending of the rigorous

linear inner design with the outline of curves cascading along the shoulders,

waist, hips and thighs.

Continues Denise, "The most

masterful part of the composition is the successful blending of the rigorous

linear inner design with the outline of curves cascading along the shoulders,

waist, hips and thighs.

"Moreover, lines and curves combine to create geometric

patterns. The semi-circle of the shoulders mirrors that of the fat rolls,

enclosing the torso into a full circle. Triangles are a leitmotif. Breasts,

lower arms and thighs are made into three triangles switching directions.

Finally, the tip of the stomach and the two upper arms form a last imposing

triangle.

"Everything in the sculpture is calculated to bring the pregnant womb into

focus. The lozenge composition emphasizes the round abdomen by featuring both

extremities of the body tapering off symmetrically on either side. The style

manipulate s the female form for showcasing the bulging stomach. Some body parts

are entirely eliminated. Among them are genitalia, navel, elbows, hands,

fingers, armpits and neck. The chest and limbs are minimized. The breasts are

flat, linear, and show no nipples. As a result, the streamlined composition

concentrates upon selected fleshy parts of the body: the upper arms, thighs, fat

rolls, and mostly, the inflated stomach. Proportions are skewed in order to

emphasize the abdomen. s the female form for showcasing the bulging stomach. Some body parts

are entirely eliminated. Among them are genitalia, navel, elbows, hands,

fingers, armpits and neck. The chest and limbs are minimized. The breasts are

flat, linear, and show no nipples. As a result, the streamlined composition

concentrates upon selected fleshy parts of the body: the upper arms, thighs, fat

rolls, and mostly, the inflated stomach. Proportions are skewed in order to

emphasize the abdomen.

"The enormous arms taper to minuscule limbs when reaching

over the stomach. The torso is lengthened to match the size of the legs so that

the womb occupies the center of the figurine. Moreover, body masses are shifted.

The switch between breasts and arms is perhaps most remarkable. The breasts are

flat but the upper arms bulge, round and voluptuous. Finally, the buttocks are

lifted to the height of the abdomen. As a result, the woman enshrines her womb

with her head bent, raised thighs and folded arms."

"The enormous arms taper to minuscule limbs when reaching

over the stomach. The torso is lengthened to match the size of the legs so that

the womb occupies the center of the figurine. Moreover, body masses are shifted.

The switch between breasts and arms is perhaps most remarkable. The breasts are

flat but the upper arms bulge, round and voluptuous. Finally, the buttocks are

lifted to the height of the abdomen. As a result, the woman enshrines her womb

with her head bent, raised thighs and folded arms."

These are compelling descriptions. But do they describe goddess figurines?

Our answer is yes. Archaeologists are constrained by their professional standards

to stick to the facts. They realize that they will never know what people prior to written words were thinking

when they created figurines like

the ones Denise just described. However, Goddesses, a site dedicated to sharing extensive

archaeological examples around the world of what could be considered prehistoric goddess-centered cultures,

know the Ain Ghazal form rather well. Goddesses, is an "archaeomythology" site, so we can stick our necks out a bit further than archaeologists.

Goddesses found at Spring of the Gazelles.

All that remains of another interesting figurine found at the site is the torso, which depicts a woman cupping, or offering, one of her breasts. It is similar to another

figure found from relatively the same time period at Catal Huyuck to the north in Turkey, a picture of which is shown directly below.

Other interesting finds at Ain Ghazal are drawn below. These drawings reveal sculptural objects created by prehistoric artists with aesthetic sensibilities

that rival modern artists.

The alien-looking twin figures from Ain Ghazal

have received worldwide publicity.

For more twin depictions

see goddesses' look at the prehistory of twins.

|